These figures highlight the growing gap between successful destinations and those that are losing relevance, emphasizing the need for thorough analysis when investing in commercial real estate, as even prime spots can become unprofitable ventures.

For example, the report mentions Gurugram’s MG Road – often referred to as the “Mall Mile” – which used to have five large shopping centres in close proximity. Inevitably, only the best-located and the best-managed mall managed to retain healthy footfalls, while the others fell behind. Whenever too many shopping centres compete in one catchment area, the weaker ones lose out on shoppers and tenants, entering a vicious cycle of decline.

Another example from the report discusses the early shopping centres on MG Road in Gurugram – once the city’s go-to retail stretch. They lost their charm as newer destinations like CyberHub and shopping centres on Golf Course Road popped up nearby.

Ghost shopping centres in India

Ghost shopping centres are defined as places where no retail or activity centre exists, they are just empty spaces.

According to the report, there are a total 15.5 million square feet of ghost shopping centres, with about 11.9 mn sq ft in Tier 1 cities, underscoring that even the most mature metro markets are not immune from this trend. In Tier 2 cities, ghost shopping centres make up 3.6 mn sq ft.

The report highlights that many of the first-generation shopping centers from the early 2000s are now empty shells, struggling to compete with newer, better-managed properties.

In Tier-2 cities, the report points out the problems arise from thinner brand pipelines, weaker anchors, and operational challenges. However, these cities also have a strong consumer appetite and aspirational demand, which opens up opportunities for effective repositioning or reinvention.

The report indicates that quality has emerged as the decisive factor in retail success.

Grade A shopping centres outperform consistently, while lower grade assets struggle to keep tenants and attract consumer interest. This polarisation defines the present landscape.

The report said: “The challenge, however, is what happens to the rest. As space in Grade A centres becomes scarce, attention turns to underperforming assets, the ghost shopping centres, whose dormant potential may hold the key to the sector’s next wave of growth.”

Why shopping centres, malls fail

According to the report, despite the initial hype, many shopping centers and malls in India have faced stagnation or even closure due to structural flaws in their concept or execution. Some common causes include:

Poor catchment planning and oversupply

Some shopping centres were constructed in locations that lacked a sufficient immediate customer base, or in markets oversaturated with competing retail projects.

A prime example is Gurugram’s MG Road which once had five large shopping centres in close proximity. Ultimately, only the best-located and best-managed centre continued to thrive while others declined.

Whenever too many shopping centres compete in one catchment area, the weaker ones suffer . In smaller cities, during the 2000s, developers sometimes overestimated future demand and built multiple shopping centres where one would have sufficed – leaving several half-empty almost from the start.

Also read: Man buys a plot on 99 years lease in auction, 3 years later govt imposes annual lease rent; he fights back and wins in Rajasthan HC

Ageing infrastructure and lack of upkeep

A number of first-generation shopping centres opened in the early/mid-2000s, did not keep pace with evolving consumer expectations. As shiny new complexes opened elsewhere, older centres that failed to renovate or reinvent themselves, saw patrons drift away. Thus the cluster of early shopping centres on MG Road in Gurugram lost appeal as newer destinations like CyberHub and shopping centres on Golf Course Road emerged .

Typically, shoppers naturally gravitate to newer options if no updates are made within 10–15 years of opening.

Design flaws and poor layout

The physical design and layout of a shopping centre can make or break its fortunes. Centres with confusing layouts, dark corners or dead-end corridors, insufficient signage, or lack of natural light and ventilation tend to discourage repeat visits. Retailers in the “hidden” pockets, losing out on foot traffic, underperform and eventually exit.

Another issue was with the “bazaar-style” strata-sold shopping centres with too many small shops sold to individual investors. These often end up looking chaotic with no space for large anchor stores, undermining the shopping centre’s ability to draw crowds.

Strata ownership model issues

Quite a few underperforming shopping centres in India suffer from fragmented ownership. In such projects, the developer sold shop units to numerous investors, often as a financing strategy during construction.

However, without unified ownership and management control, maintaining quality and a curated tenant mix becomes nearly impossible as each unit owner leases to whoever will pay rent, leading to an ad-hoc mix of tenants, inconsistent storefronts, and no collective marketing.

As overall standard can’t be controlled effectively, many such properties become nothing more than collections of unrelated small shops rather than a cohesive shopping destination.

Anchor tenant loss

The exit of a major anchor tenant – such as a prominent department store, hypermarket, or multiplex cinema – can deal a severe blow to a shopping centre’s viability if not addressed swiftly. Anchor tenants are key footfall drivers; when one pulls out, the reduced traffic often causes sales for smaller stores to collapse, prompting a broader exodus of tenants. In many cases, this has proved to be fatal.

Once the big draw leaves, a domino effect kicks in where other retailers “bleed” and vacate, sometimes forcing the centre to shut down entirely if a suitable replacement anchor cannot be found in time.

E-commerce impact and external shocks

The rapid rise of e-commerce in the last decade hit mid-tier shopping centres particularly hard – especially those that did not differentiate themselves with experiences or exclusive offerings. Commodity retail segments (books, music, basic electronics, etc.) saw declining footfall as consumers shifted those purchases online.

Centres that were heavily reliant on these stores struggled to generate reasons for people to visit, aside from perhaps a food court or cinema. Those draws alone aren’t always sufficient if the centre is poorly located or otherwise unappealing.

Additionally, unforeseen shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic delivered a heavy blow to weaker shopping centres in 2020. Many properties, already financially shaky, did not recover post-lockdown. Lacking resilience in terms of tenant mix or customer loyalty, they failed to bounce back after months of closure.

Regulatory and legal troubles

Sometimes, external administrative issues can lead to the downfall of a shopping centre. Projects stuck in long legal disputes (for instance, litigation over land titles or zoning, or delays in getting occupancy certificates and approvals) could not lease space effectively, resulting in empty buildings.

This was the case with the Grand Sigma Mall in Bengaluru, which was caught up in legal issues around land use. It was never able to fully open and was ultimately demolished – an extreme case of value destruction.

These kinds of regulatory snags or compliance failures can scare away retailers and visitors, causing even a well-designed centre to turn into a dead asset if the issues aren’t resolved promptly.

Shopping Centres “die” when their core value proposition falls apart – be it from a flawed location, mismanaged operations, eroded consumer trust, or just economic factors making them unsustainable.

The report said: “Unfortunately, India has accumulated dozens of such struggling or closed shopping centers, especially in metro suburbs and smaller cities from the first wave of mall construction.”

The 5.68% rental yield opportunity in commercial retail space

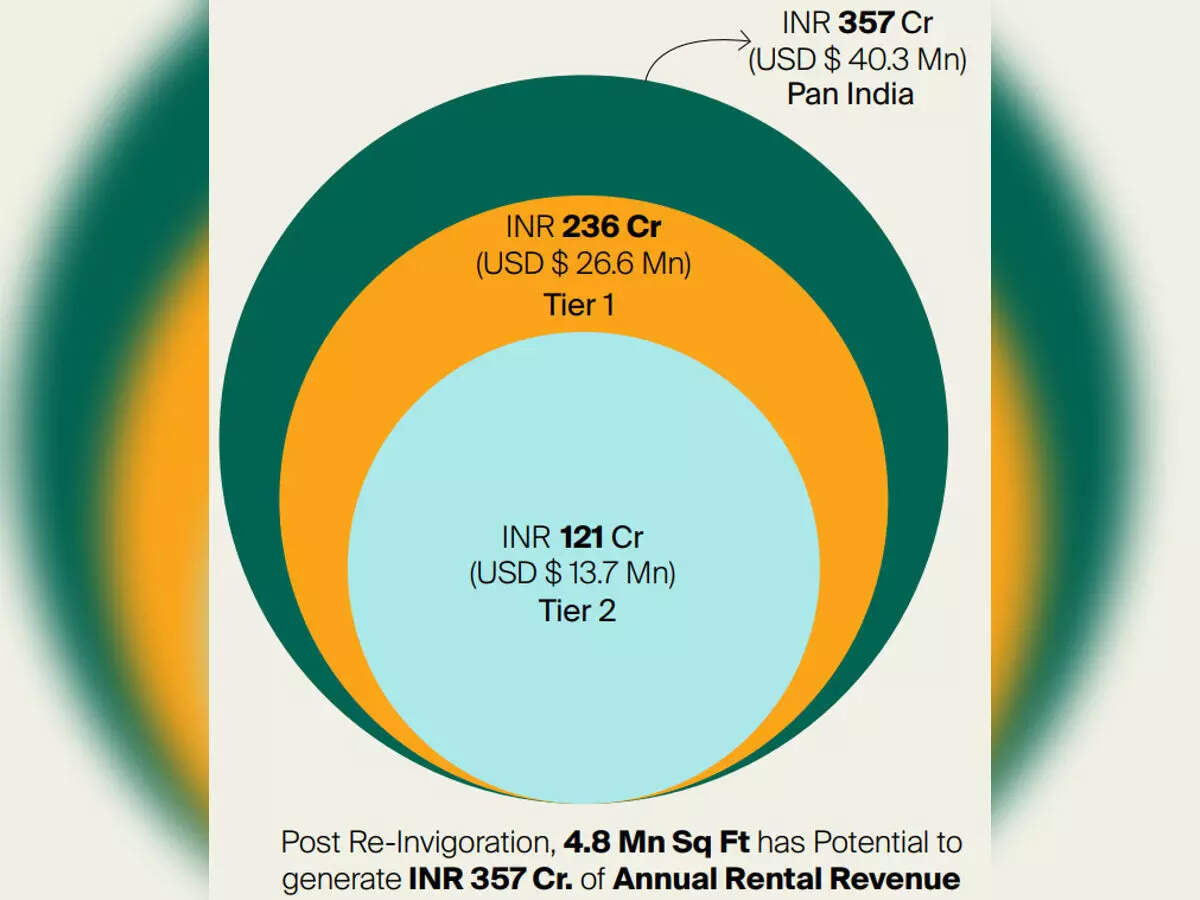

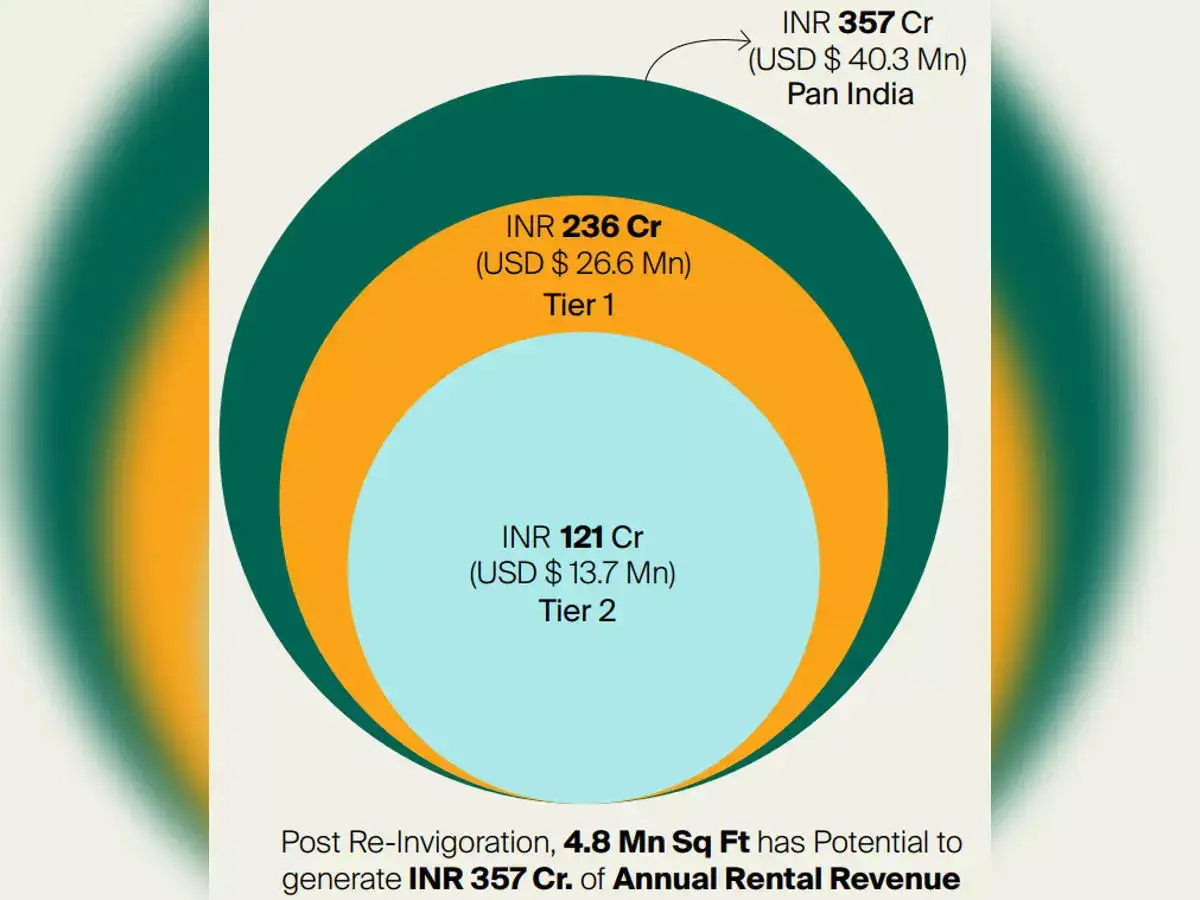

The report said that reviving ghost retail spaces could have a significant upside. They estimated that about 4.8 mn sq ft of the currently dormant shopping centre inventory in India has great potential for a successful revival.

The report said: “If these spaces were redeveloped and reoccupied, it could generate approximately Rs 357 crore in overall annual rental revenue – equivalent to around USD 40 mn of revenue each year.”

The report said that this dormant retail opportunity, if unlocked, would not only boost the retail turnover in their respective cities but also create jobs, improve shopper choice, and enhance real estate value in those micro-markets.

How the 5.68% rental yield opportunity works

The report said that most of the immediate opportunity lies in the major cities (Tier 1 metros contribute roughly two-thirds of the potential at Rs 236 crore), but a significant one-third (Rs 121 crore) comes from high-potential assets in Tier 2 cities.

For investors, these numbers hint at possibly attractive returns. The report said that acquiring or partnering with a distressed shopping centre can come at a fraction of the cost of greenfield development in a prime area, and once revitalised, can generate healthy cash flows.”

Beyond revenue, Knight Frank said that they have also analysed 15 shortlisted shopping centres in depth and recalculated their tentative return on investment (RoI).

The report said: “Our findings indicate that these centres, once reinvigorated, have the potential to generate a rental yield of 5.86%. This reinforces the attractiveness of reinvigoration as an investment play, offering not just revenue uplift but also stable, sustainable yields that compare favourably with other real estate asset classes.”

Knight Frank

Source: The report (https://content.knightfrank.com/research/3062/documents/en/think-india-think-retail-value-capture-unlocking-potential-2025-12566.pdf)